There’s a surprising amount that we don’t know about whale sharks even though they’ve captured the world’s imagination and swimming with them has catapulted to the top of many people’s bucket-lists.

We don’t know where they mate, where they give birth, if they care for their young or exactly how long they can live. And although scientists have recorded their unusual pattern of deep diving, they’re still trying to fully understand why.

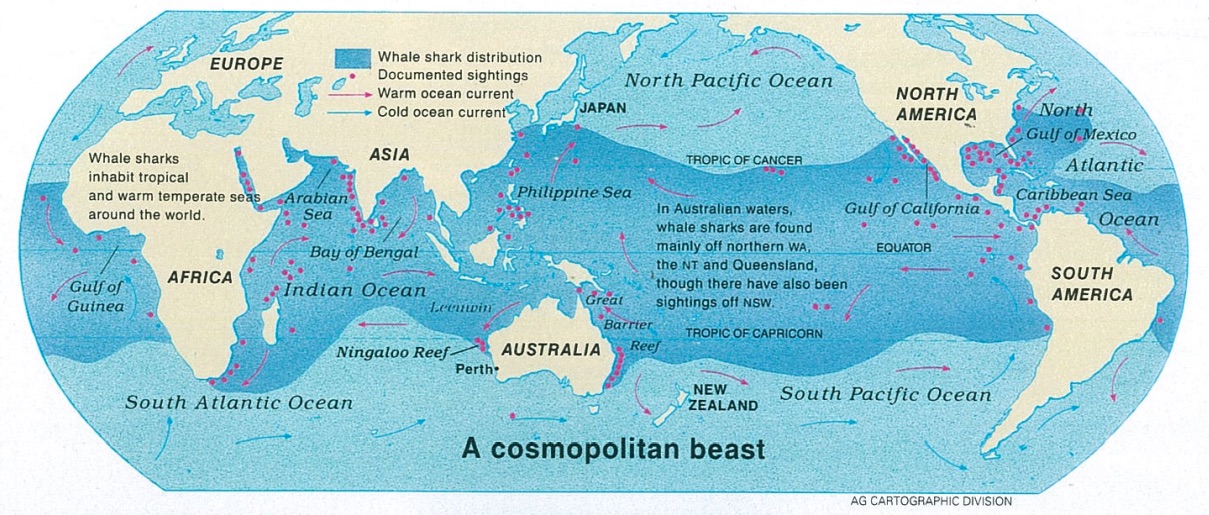

“Whale sharks spend their entire lives moving around nutrient-poor tropical waters,” says Perth-based Dr Mark Meekan, Senior Principal Research Scientist at the Australian Institute of Marine Science. “There probably hasn’t been a giant filter-feeding fish of that size living in tropical waters since the end of the dinosaur period, which makes the whale shark an enigma.

“Their whole metabolism is set by the warm water around them so they need lots of food to keep their basal metabolism going.

“We’re interested in how and why they stay in tropical waters. And what we learn from this research could also tell us about the whole sweep of evolution, how life in the oceans has evolved to culminate in giant filter-feeding sharks and whales that have emerged from very different origins. We’re talking about convergent evolution, where two species with different ancestors develop similar characteristics. There are so many clues to uncover both about our past and our future.”

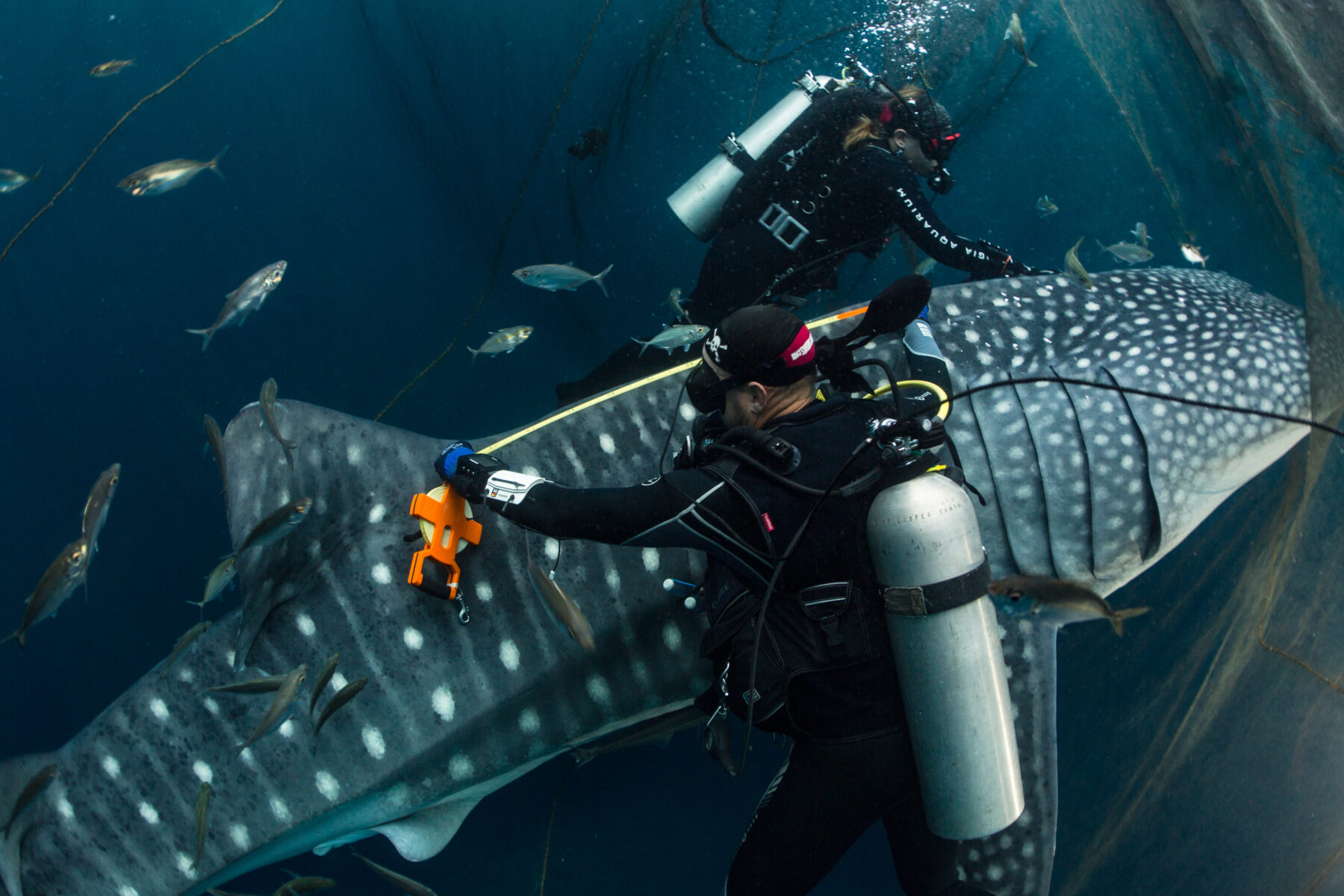

Dr Mark Meekan removing parasitic copepods from the lips of a whale shark for a genetics study, Ningaloo, Western Australia. Image credit: Wayne Osborn

Mark and other Australian marine scientists have been researching whale sharks, officially listed as endangered by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List, for more than 20 years at Western Australia’s Ningaloo Reef. However, it’s only been six or seven years since they started liaising with international and Indonesian scientists to conduct whale shark research in Indonesian Papua’s remote Cenderawasih Bay, which has an estimated population of 135 mostly young male whale sharks, according to a research team from the World Wildlife Fund for Nature (WWF) Indonesia.

Cenderawasih (Bird of Paradise) Bay has become known as one of the best places in the world to swim with whale sharks. I swam with eight recently, one showing its research tag, as they wove all around me to filter feed bait fish thrown from a traditional bagan fishing platform. It was the most spine-tingling experience.

Whale shark feeding under bagan platforms in Cenderawasih Bay, Indonesia. Image credit: Abraham Sianipar

Looking like a big gulp out of the north coast of Papua in the far east of the Indonesian archipelago, Cenderawasih Bay was an ancient sea during the last Ice Age, separated from the flow of the Pacific Ocean. As a result, it has a high percentage of endemic coral and fish species found nowhere else on Earth. Indeed, renowned ichthyologist Dr Gerald Allen, a former curator at the Western Australian Museum and a consultant with Conservation International, calls Cenderawasih the Galapagos of the East because of the richness of its marine life.

This is why the whale sharks, particularly fast-growing juvenile males, are here because it provides cost efficient foraging, the minimum energy output for the maximum energy intake. They can keep their growth rate up easily under the bagan nets.

Indonesia declared whale sharks a protected species in 2013 and, since 1993, Teluk Cenderawasih National Park, Indonesia’s largest marine park, has protected 14,000 square kilometres of the Bay, an area about the size of Greater Sydney.

The fishermen on Cenderawasih Bay’s bagan platforms, anchored off shore for months at a time, have enjoyed a longstanding relationship with the whale sharks, which they believe bring them good luck. They give them a small portion of their daily catch to keep them around. Given the increased interest among adventurous divers and snorkelers wanting to swim with whale sharks and, monitored by Conservation International and the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) both of which are very active in the area, these fishermen now also receive a supplemental income from allowing sustainable tourism ventures to offer whale shark swims.

Whale shark in bagan net, Cenderawasih Bay, Indonesia. Once the shark has left the net it is pulled up. Image credit: Abraham Sianipar

Tagging and Bagging

Whale shark scientists, like the trailblazing New-Zealand-based American Dr Mark Erdmann, who is now the Vice President of Conservation International’s Asia-Pacific marine programs, Mark Meekan, Masters student Abraham Sianipar and PhD student Megan Meyers, have also benefitted because the whale sharks are so relaxed in these bagan environments that it’s very easy to tag them to learn more about their behaviours. They also regularly come back to the same bagans, which makes it easy to retrieve the tags.

“Our tagging techniques in Cenderawasih Bay have been quite ground breaking,” says Abraham, who was in charge of the tagging process for all the Australian studies. “It’s opened up a lot of new doors of potential study in the future.”

There are many places around the world with transient whale shark aggregations following seasonal food sources. This is true in Ningaloo Reef, Christmas Island, the Red Sea, the Galapagos, the Seychelles, Donsol in the Philippines, Isla Mujeres in the Caribbean, Baja California and elsewhere.

By comparison, many, but not all, of the whale sharks hang around Cenderawasih Bay. The scientists are trying to understand why many stay but also why some go, and where they go to.

Whale shark measuring and tagging, Cenderawasih Bay, Indonesia. Image credit: Abraham Sianipar

Anatomy 101

First of all, a little whale shark anatomy lesson.

The whale shark is not a whale but the world’s largest fish with cartilage rather than bone for a skeleton. It can grow to 18 metres and weigh more than 30 tonnes. It uses its gills to extract oxygen from the water.

A mainly pelagic species living in warm oceans, it’s a slow-moving, deep-diving filter feeder with a large wide mouth that uses 20 filter pads that lie above the gills to feed on plankton, crab larvae, tiny fish and krill. It can either ram filter feed horizontally or suction feed vertically and in both cases the filter pads separate the food from water that then passes over the gill.

Each whale shark has its own unique polka dot spot pattern on the skin, rather like a fingerprint, which can be used for identification and tracking. The local villagers in Cenderawasih Bay call it gurano bintang or starry shark since the spots look like the stars in the Milky Way.

Each whale shark has its own unique polka dot spot pattern on the skin.

Travelling Patterns

Megan Meyers has recently submitted her PhD thesis at the University of Western Australia examining the travelling patterns of the Cenderawasih Bay whale sharks. It is based on the retrieval of 22 fin-mounted satellite tags that provided unusually long track durations averaging a year of transmitted information. She concluded that their behaviour varied depending on the type of habitat they occupied whether it was bay, coastal or offshore but the sharks did not appear to migrate from the bagan nets for seasonal reasons.

She found that the whale sharks in offshore habitats travelled more and occupied deeper waters than those within the bay. It appears that the younger male whale sharks are more opportunistic and, for many, the ready supply of food at the bagan platforms in Cenderawasih Bay was reason enough to stay.

Megan Meyers and whale shark surrounded by bait fish. Image credits: Megan Meyers.

Bait fish on bagan platform. Image credits: Megan Meyers.

Megan discovered that just before sharks migrate they tend to do some deep dives. She identified 335 “extreme” dives to over 700m depths, which her analysis suggests are made for a variety of reasons that may include navigation, thermoregulation and foraging.

These deep-diving patterns are what Abraham studied for his Master’s thesis on the behavioural ecology of whale sharks. His work was based on using more complex accelerometer tags (which function almost like FitBit loggers for an unprecedented month-long behaviour study) on just three whale sharks that not only showed where they went but also what they were doing by measuring their resting, swimming and migrating behavioural states and thereby estimating their activity and energy expenditure.

As his supervisor, Mark, says, “We know where most of them are going. What we’re trying to understand is what their daily lives are like in the ocean, while hidden from the human gaze. These sophisticated tags give us a window on each shark’s direction, pitch and orientation… its movement in three dimensions… and they tell us how much energy it’s requiring to do what it’s doing.”

Abraham Sianipar affixing a tag to a whale shark, Cenderawasih Bay, Indonesian. Image credit: Abraham Sianipar

During the day, whale sharks out in the open ocean dive from 200–500m to feed on a layer of shrimp and small fish that forms in this deep water to escape predators. Whale sharks cope with this cold environment by warming at the surface both before and after these dives, allowing them to feed before they lose too much heat. Occasionally, the sharks dive to great depths, up to 2km down, where it’s very cold and dark and they experience extremely high pressure.

“The current hypothesis is that there is not one reason for these deep dives,” says Abraham.

“My research showed that there is quite a bit of diversity in their behaviour and they are actually spending a lot of time at depth, which hasn’t been reported before, so it’s quite exciting. We’re seeing some interesting movement but we still don’t know what or why. The data is so dense so we’re working with colleagues to interpret it in more detail. It’s still a puzzle.”

Although whale sharks may be deep diving to forage, regulate their temperature and avoid predators, “navigation appears to be the most plausible reason,” says Mark. “There are magnetic bands in the Earth’s crust that can be detected more easily by animals at depth. It is possible that whale sharks do these deep dives to remove the noise of the ocean currents so they can get a clearer picture of that magnetic field to determine where they are.”

However, they need to warm up again on the surface. One other disturbing insight of a range of collaborative research is that many whale shark satellite tracking tags stop transmitting in the middle of high volume container shipping lanes. These results point to potentially high levels of undetected or unreported ship strikes, which could explain why the already-listed-as-endangered whale shark populations continue to decline despite worldwide protection, a reduction in whale shark finning, and low fishing-induced mortality.

“We hope that our research will help highlight the value of protecting whale sharks not only as an ancient species but also as a source of income for remote communities from sustainable tourism initiatives,” says Abraham.